This is the fourth post on the series, if you haven’t seen the other posts yet, I recommend you read them for added context.

In this post, we will review the decisions and methods related to DevOps of Sharp Cooking. To summarize to the extreme, DevOps is all about people, processes, and tools. However, this post will focus mostly on processes and tools.

Before we begin, keep in mind how simple Sharp Cooking is. Its DevOps is also simple since nothing warrants a more complicated approach. The key here is that while it is simple, it does exist and it is enforced.

Hosting

I initially leveraged the GitHub pages feature available in any public repository to host the Sharp Cooking app. GitHub pages is free and very easy to set up: upload the files in a repository or sub-folder and configure GitHub pages to serve the folder. You may also use GitHub Actions to compile from source as needed. In any case, The resulting site is available at https://username.github.io/repository-name.

When the Sharp Cooking API was introduced, it also created a challenge to using GitHub pages. APIs are not supported on GitHub pages. Back to the original idea of rewriting the app, whatever solution I used, it should be free so I first tried Azure App Service as it does have a fairly generous free tier. It does come with limitations, as should be expected of any free offering. The primary limitation that made using Azure App Service hard to use is that it does get stopped when it is idle for a while. That meant that downloading a single recipe could take as long as 40 seconds because of the cold start. Interestingly, converting the App Service app into an Azure Function yielded much better overall performance so I switched to that.

I wanted to publish the API and app together so I also looked into Azure Static Web App. It does offer, well, static web app hosting but it also provides integration with Azure Functions while still having a free tier offering. Given the very minor changes required to the code base, I decided to pivot and use Azure Static Web App instead of GitHub pages.

Development Platform

It’s been a long time since I used anything other than git for Source Control. Since I see no reason to change this, Git is used for Sharp Cooking source control. Because the project is also Open Source, GitHub is used as the development platform.

The decision to use GitHub is not as simple as it seems. Part of what will be discussed later in this article are the other tools provided such as GitHub Actions and Issues.

The runner-up on this decision was Azure DevOps. It allows for git-based source control, Azure Pipelines has probably the best CI/CD tools I have used, and Azure Boards are much more comprehensive than GitHub. However, GitHub is more popular for open-source projects and while there is no official word from Microsoft, it is my opinion that Microsoft will eventually move away from Azure DevOps in favor of GitHub.

Issues

Currently, GitHub Issues is used for both development and user feedback. While I realize that not all users have an account in GitHub nor necessarily know how to use it, it is very convenient and it does get the job done. As the app and user base grow, I expect this area of the project will grow too.

Git branching strategy

Currently, there is only one developer on the project. Me. A branching strategy does sound like overkill at this point, but pushing directly to main branch makes my skin tingle like I got spiders crawling all over me. If we have to name a strategy, GitHub flow is the simplest strategy that fits the current project’s needs. If you are unfamiliar with it, GitHub flow uses branches for all development, the branches are taken off of the main branch and always merged via pull request back into main. The primary requirement is that main is always deployable. If you are interested but unsure how it works, read this great comparison between Git Flow and GitHub Flow.

To summarize, the main branch is protected and code can only be merged into it via Pull Requests. Every time a pull request is created, a Git Hub Action is executed that will build, validate, and publish a version of the website for additional manual review and testing. This strategy emphasizes the importance of proper testing. If you are confident that passing tests means a good version then this approach might be a great fit for you.

Versioning

The original app was updated infrequently. As often as once per week and sometimes once in several months. This release cycle made versioning and release notes important. The version number used was semver with Major.Minor.Patch. In fact, the very latest version of the app was 1.7.0.

One of the small annoyances related to app releases is manually setting the version number before a release. I must have forgotten this step several times and that created additional work because a secondary release was often needed to fix this mistake. With SharpCooking, I wanted to automate this process but keep using semver. For this, I used GitVersion which is a convention-based tool that uses git log to generate a semver version number.

In the case of SharpCooking, I decided to prepend commit messages with a few keywords that helped GitVersion to determine the version number upon every commit. The configuration for GitVersion looked like this:

| |

Finally, the version is actually generated on the CI / CD of the main branch. The following steps were used in GitHub Actions to install GitVersion, generate the version number, and store it in a .env file the app can read at runtime:

| |

CI / CD

A key requirement for me was to automate the validation and deployment of Sharp Cooking as much as possible. Therefore, a key component of the DevOps strategy was CI / CD workflows. GitHub Actions is very powerful and allows for everything Sharp Cooking needs:

The steps below are a representation of the build and do not necessarily occur in the order depicted.

- Perform Static Code Analysis with SonarCloud

| |

- Calculate and apply version number (See Versioning)

- Compile and package the application

- The compilation is done by Static Web App so the build and deployment are a single step.

- Deploy Web app and API to Azure

| |

- Execute unit tests for API using pytest

| |

- Execute end-to-end test suite using Playwright

| |

Additionally, the workflow should be executed for each PR created and when the main branch is updated. For PR validations, the deployment should create or update a staging environment in Azure. When triggered by a commit in the main branch, the deployment should update the production environment.

See the workflow in the repository for full reference.

Testing

Deciding on the appropriate approach for testing Sharp Cooking was very hard. There are two software components to test: the SPA app and the API. I honestly haven’t had much success with unit tests for SPA applications. The tests often become shallow and you end up writing too much test code for too little benefit. In general, I prefer to test code based on what (or who) is consuming it. If I have a shared piece of code that is used by many components that should probably be unit tested. For UIs, I see a lot more value in end-to-end testing with minimal to no mocking. As for the API, that makes much more sense to unit test. The Sharp Cooking API is especially easy because, again, it is so simple.

I chose Playwright for the end-to-end testing of the SPA app. I’m planning an article about using Playwright to test Sharp Cooking so I will not add a lot of details in this post. However, I’m truly in awe of how good Playwright is. The tooling is excellent, the tests are very stable with very little flakiness, and the documentation is great.

Example Playwright test:

| |

As for the API, I used pytest. My python experience is fairly shallow, however, pytest did the job just fine and I enjoyed using it.

Example API test:

| |

Change log

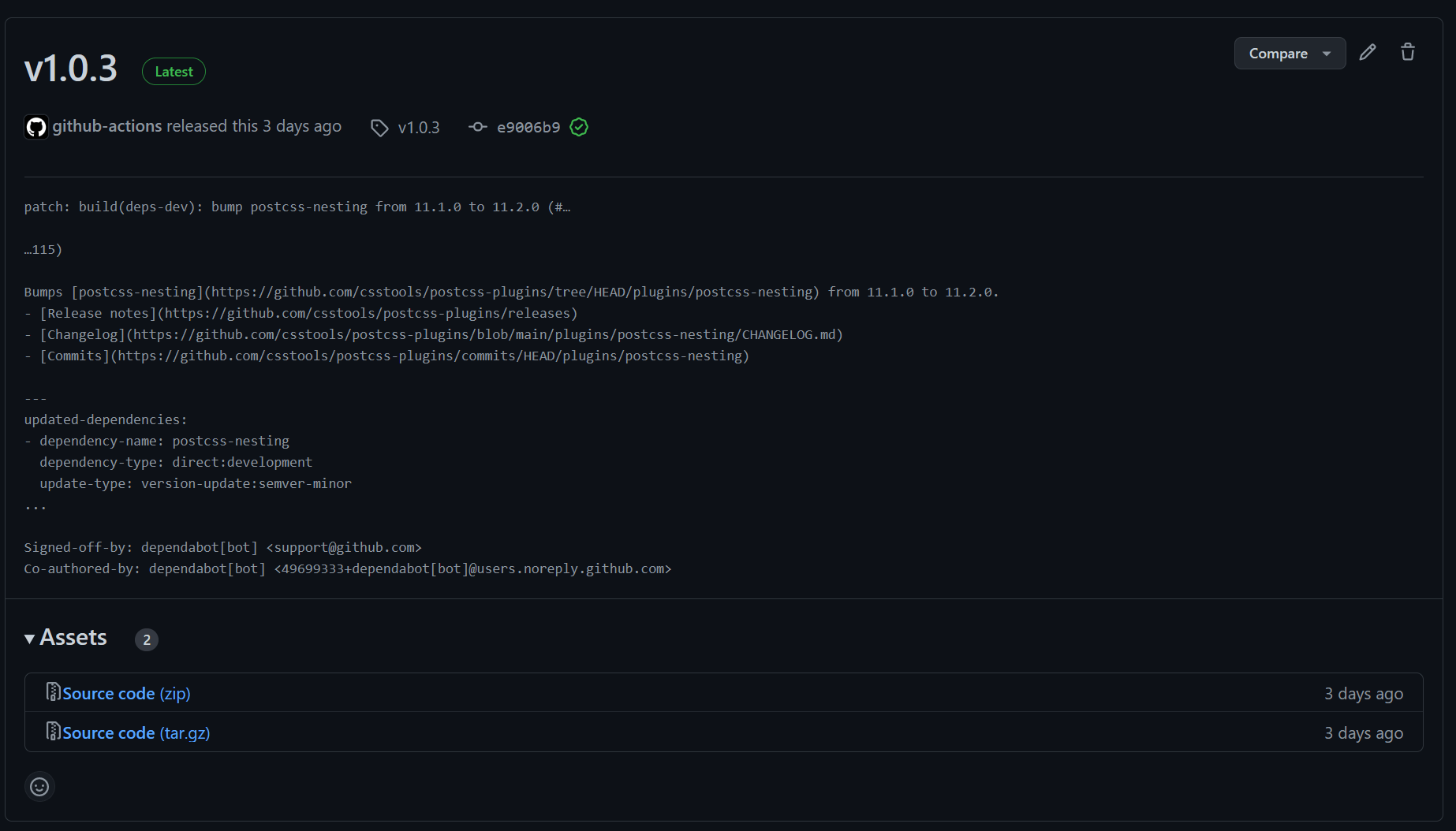

The original app exposed a list of changes for each release. However, I expect the new app to be released more often given the DevOps choices that were made. Also, instead of having a dedicated page in the app’s landing page, the new change log is exposed via releases in GitHub:

The release creation is currently automated in the app’s workflow. The version generated by GitVersion is used as the release number and tag name:

| |

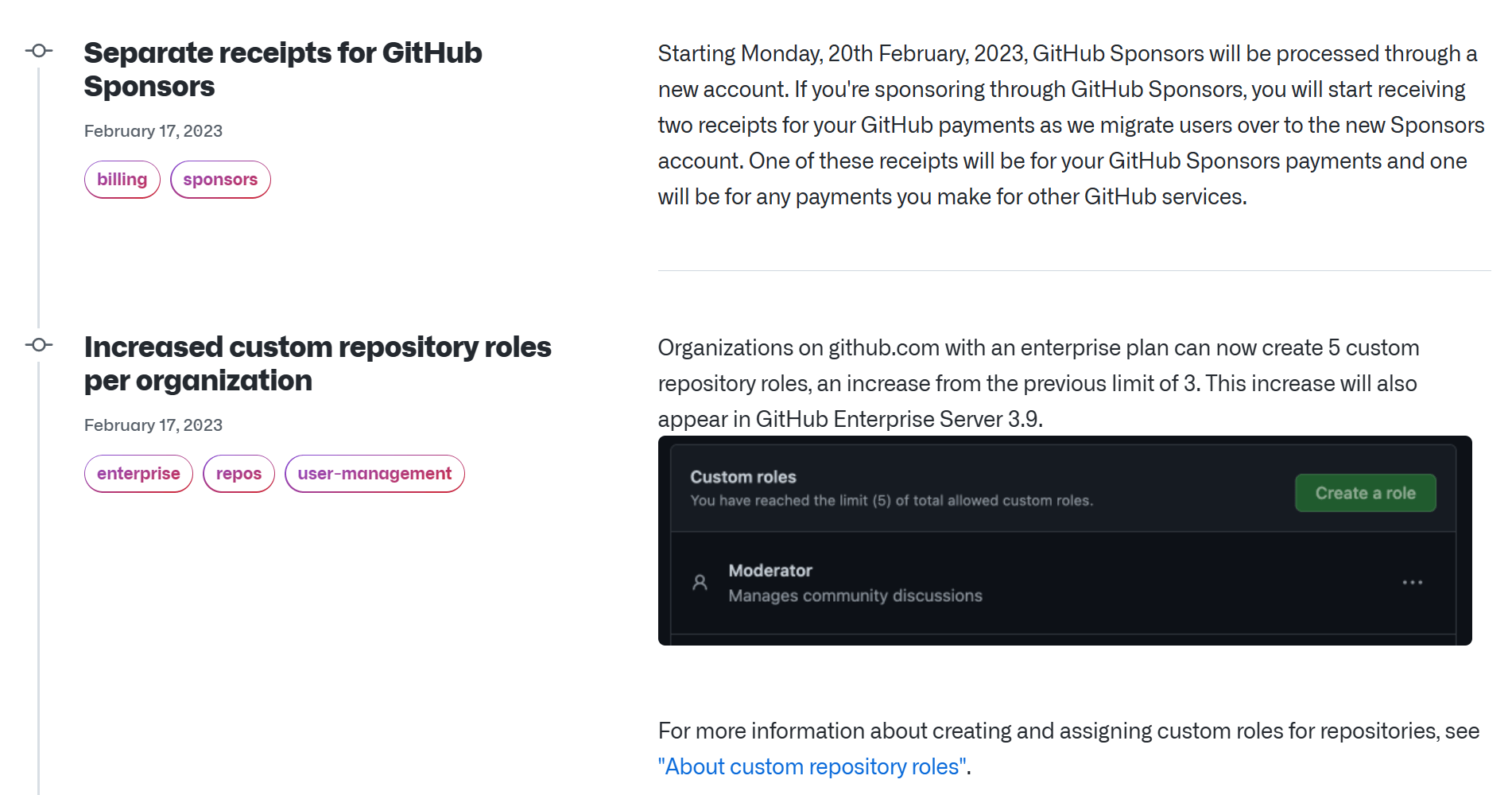

I’m not entirely satisfied with this approach. Each release generates a named version that has a short life, usually. Therefore, having a name for each release doesn’t add anything. I’m partial to how GitHub itself does its change log. Instead of focusing on versions, it focuses entirely on the features released:

I plan to return to the changelog soon and perhaps it will change into a changelog focused on features instead of versions.

Dependency updates

Dependabot helps automate dependency updates in GitHub repositories. It offers 2 features that are very important to Sharp Cooking: version updates and security updates for dependency packages. Currently, Dependabot is configured like so:

| |

Monitoring

This is an area where Sharp Cooking is lacking severely. As of now, there is no real monitoring for the published app nor is there any type of usage analytics. The challenge is about cost and compliance, Azure App Insights is great, but there is no free offering for it. As for analytics, Google Analytics is free however is notorious in the EU where the original app had users so I don’t want to use it yet.

This is another area where I expect significant improvement soon.

Documentation

Nobody likes to write documentation. I know I don’t. Yet, it is sometimes as important as the code itself.

Sharp Cooking’s documentation is available at https://sharpcooking.net. The website was created using Hugo, just like this blog, and Geekdoc theme. The code for the documentation is also open source and available at jlucaspains/sharpcooking-docs.

The website is composed of a simple app landing page:

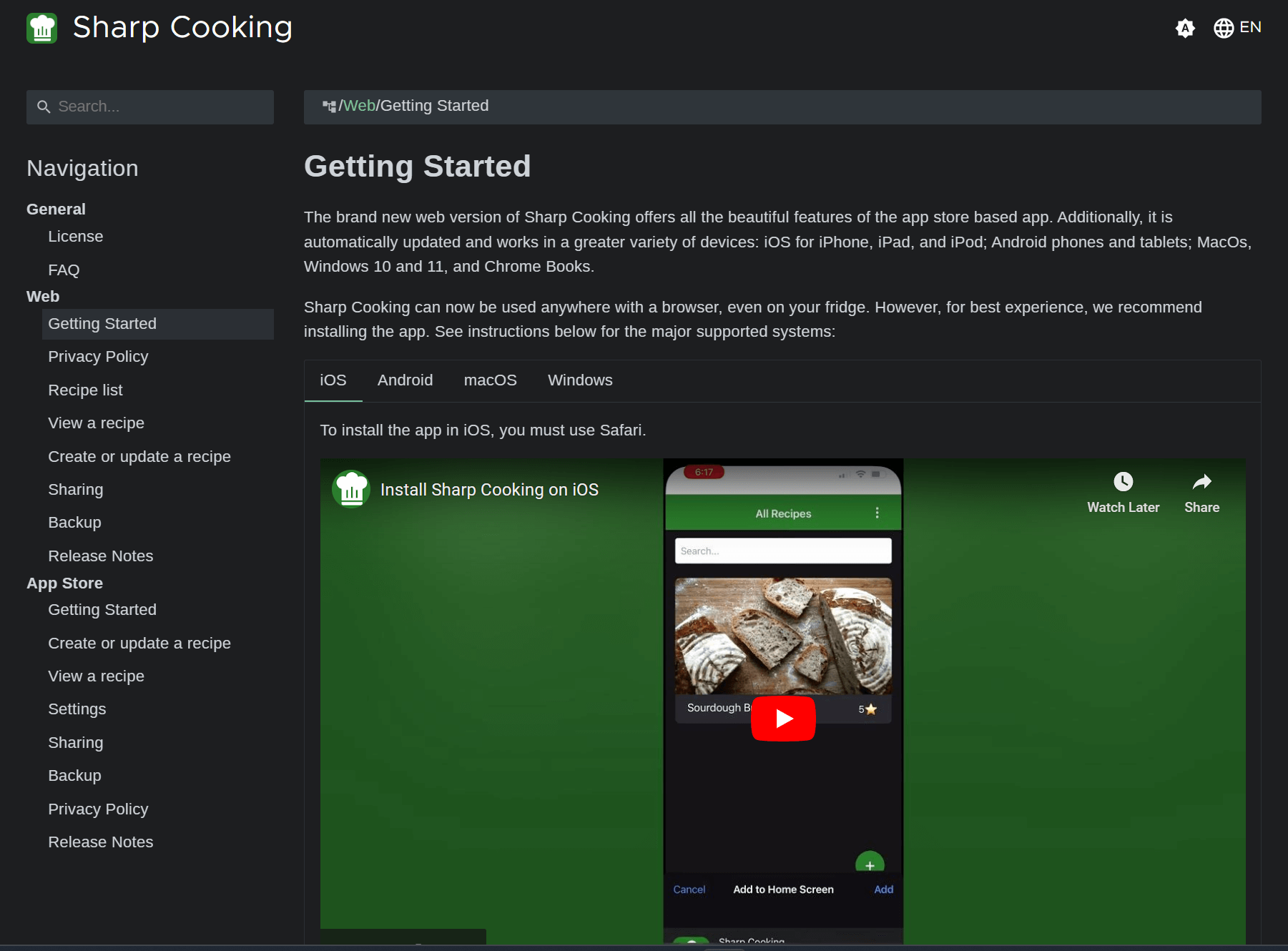

And a traditional documentation page where topics are on the left and content is on the right:

Closing

This was one of the longest posts I’ve ever written. I love DevOps in general and I had a lot of fun setting this up for Sharp Cooking. I also had quite a bit of fun writing this post.

Next and last post on the series: The fun with Playwright